The fact that The 1975 have been playing together since 2002 creates a different expectation to this debut album than what most get, although it's stupid to pin 10 years to any album, especially one from a band that doesn't wear it on it's sleeve. The 1975 have only been releasing material since early last year, culminating in four EPs; with pickings from them alongside new material going into this debut album. This 10 years doesn't confuse the music as much as it confuses the band itself; even with so much time together The 1975 don't have an identifiable image; I found out about the band from two fan girls on facebook and not a marketing team, and even after spending time with their album I get the feeling The 1975 still don't quite know what they're gunning for.

The sound here has a solid beat, and a couple of the riffs flow well too, not that any of it sticks in the mind; the compositions are slower than your average pop and simpler too. The whole album has a quiet, lonely feeling that would work better in a bedroom confessional-type setting, but the band's aim is too broad to tap into this. Instead the production has a synthesized 80s feel to, so much that the opening of "Heart Out" sounds like it could quickly morph into Paul McCartney's "Wonderful Christmas". It blends all the instruments together, adding more weight to the guitars and making everything shake when the drums hit, yet losing individual elements in the mix, allowing tracks to drone on, and sometimes burying Matthew Healy's vocals underneath the production, making them near-impossible to understand.

Yet for a band so focused on (and who's highlights come with) glistening pop, the band feels insecure in giving it to us. The opening track, brain shatteringly called "The 1975" is the opening track of a very different album, the over-bearing production qualifying the track as psychedelic-lite. Tracks like this show up throughout the album like the instrumental "12" (it's the 12th track on the album, get it?) there for padding, not because there isn't enough music here (there's 16 tracks in total) but to make The 1975 look bigger than they are. "Menswear" takes two minutes for the vocals to kick in yet when we get there it's a pop track as throwaway as most of the others; The 1975 want us to believe they're a lot more than just a pop band, at least something more experimental and meaningful, and they've certainly listened to albums that have done that before - the universe-of-possiblilities-type scope of instrumental "An Encounter" brings to mind "Here Comes The Night II" on Arcade Fire's latest - but they never put enough meat on the bones to make this album anything more than disposable pop, which they almost look down on.

When they're not looking down but accepting simpler arrangements The 1975's real talents come through; the highlights are "The City" and "Heart Out" which are fun if unmemorable. The names of many tracks are simply the name of the subject we're on: "M.O.N.E.Y" "Sex" "Girls" "Talk!"; a lot of the lyrics here don't illicit much brain movement but when they're writing well The 1975 come across as a more bleak version of OneRepublic by which I mean they've got the pop-rock formula down pretty well: little small talk, focus on the emotionally connecting lines. The best lyrical work here is in "M.O.N.E.Y" which describes a bad night with too much drinking, the lyrics never transcend quick-relations but they throw out lines that flash straight in your eyes (ears?): "He doesn't like it when the girls go/Has he got enough money to spend?" and "He's just been barred for that blues he was smoking/And then he barks: it's my car I'm sleeping in", and later on the band goes into even more relatable territory, at least to youngsters who aren't aware their youngsters, with lines like "She's got a boyfriend anyway" and "Why don't you take your heart out instead of living in your head" which border on manipulation but for the purposes of the songs here gets the point across perfectly.

What I'm trying to sum up here is that The 1975 don't/doesn't harm anyone, although I really wish it/they did. It want's to be pop but there's catchier stuff out there, and despite this being a band that's been together for 10 years there's much more confident stuff out there too. When the album aims for something more it just weighs it's other parts down. As a building block this debut feels blank, and doesn't really point to any future for the band if they continue to be on the fence like this. It's got catchy moments though, which is really all I can say.

Wednesday, 27 November 2013

Sunday, 24 November 2013

Lester Bangs: My Drug Punk Hero

Reading "Main Lines, Blood Feasts and Bad Taste" I haven't even got to any of Lester Bangs published articles, I'm still on clippings from some auto-biography pieces he wrote in his youth, titled "Drug Punk" and I can barely get through it because I just wanna run to the computer and write. I haven't felt this excited since reading Psychotic Reactions, and this is just Lester's scribbles before he got published. So I'm telling you right now if your an aspiring writer, you want to be big and have lots of people reading your writing and your giving it a go but your not quite there yet, then let me tell ya' you need a Lester Bangs. You need someone who makes you want to write after you read one sentence. Who rambles and blabbers on but to your eyes it's made of gold. It doesn't matter who it is, some romantic a hundred years gone or some guy who wrote his first blog post last week, or even one of the greats: Hemingway or Fitzgerald, it doesn't matter, you just need one, because reading from that writer you understand why you've got to keep on typing away. Not because you want to write that good, although you should be aiming for that, but because if writing your own stuff ever creates that same feeling as reading their's then you'll know your doing it right. Lester Bangs is the reason I write, and my drug punk hero.

Happy writings!

Happy writings!

Tuesday, 19 November 2013

Mike Leigh's Naked (1993)

In the first scene of Mike Leigh's Naked we see Johnny (David Thewlis) raping a girl before quickly driving to London (from Manchester) to avoid the consequences. He goes to the apartment of an ex-girlfriend (and her two wildly different roommates) and after conjuring up eccentric reactions from them leaves and spends most of the film walking around the London streets, interacting (and annoying) the locals, and finding himself in worse and worse predicaments; not that he ever seems to care all that much.

It's a wordy movie, made up mostly of dialogue from a wide variety of characters who don't stick around long and don't seem to affect much in terms of plot. Yet plot isn't what Naked is about, and neither is it about what makes Johnny tick; as Johnny says at one point "You've had the universe explained to you, and you're bored with it, so now you want cheap thrills and like plenty of them" before walking us through a disposable world where he remains utterly disgusted with everything he see's, and happy to tell everyone about it. It captures a time and place that doesn't seem far away but doesn't exist anymore; that old Britain, not yet commercialized into looking like the rest of the world; it's lots of old fashioned wall papers and yuppy offices. Each person lives in their own little box; the apartment in the film has three people living there but doesn't look lived in at all; it looks temporary, as if all the people living their decided the second they got there that this isn't where they want to stay; Naked is a collection of lives - a lonely night guard, a shy waitress, an easy-going junkie type - that don't feel like they're being lived yet, like they're waiting for a jump start, yet Johnny seems to be the only one who understands that-that jump start isn't coming.

London is painted as an apocalyptic wasteland, each act of unsettling human nature completely ignored by the other happening just a few feet away. All the outdoor scenes look very cold, as if it's the city that's naked; stripped of it's own soul and reduced to accepting the wasteland it's become. Millenium angst looms large, as if the countdown to 1999 has let people live without the same cares as they normally would; this is the setting of The Clash's London Calling, only it's not the government that's pressing down on everyone, the government is invisible here, it's the people themselves; a city eating itself from the inside out. Yet we keep watching Johnny, not because his bleak view lets him see what the people around him don't see, but because even though he's just as lost as everyone around him he seems to care; it would be easy to say he's given up but the torment Johnny looks trapped in stems from a disappointed with the world, and it's only a select few who have the bravery to be disappointed. He has tattered clothes and a messy excess of facial hair and through it all he looks like Jesus, and he wanders around like some sort of messiah; he doesn't give out any answers but looks like he knows them all.

The energy Johnny inspires stems simply from a sense of purpose; he's that magical layabout figure that somehow doesn't seem lost. Johnny's only real possession is his rucksack which as far as we see contains only a small collection of books, Johnny coming across very well read, and sitting there at night watching the movie it made me want to go to the book shelf and start reading right then. Because Johnny's the type of book worm everybody wants to be; not the greying professor but the man who looks like he's been into as many strange worlds as he's read. At one point he finds himself in a woman's house, checking out the book shelf; he tells her about Homer's Odyssey which she owns but hasn't read; it's hard to imagine this man sitting down and reading The Odyssey, instead he comes across as a character who was born already knowing it.

In the best shot of the film Johnny is attacked by a group of youths; they emerge from a dark alley and are masked in silhouette, as if it's the city itself that has swallowed him whole and spat him out a beaten wreck. It's a cruel joke by the filmmakers that we get to know all the characters Johnny meets and annoys, yet it's a nameless group, completely clueless to who Johnny is, that attack him. This sequence always reminds me of a news story from around 10 years ago when Thom Yorke, of Radiohead, was beaten up outside a pub in London. Both men, the real and the fictional, are symbols of angst against the modern world, and these incidents both have these men being beaten up by their own angst; the same world they look down on coming forward and reminding them that they haven't changed it at all and probably never will. That incident can be clearly heard in the sound of Radiohead's album "Hail to the Thief" a peak of paranoia and going off the front cover: capitalist angst. That music would go well with Naked, although even better is the film's melancholic score, which manages to follow Leigh's wonderfully realistic emotional pallet beat-for-beat.

Yet by the end of the film we're at the exact place we started off, more or less, but it feels like we've progressed. Johnny gains nothing from his visit to his ex other than the knowledge of what she's doing now; no relationship after the end credits is pointed to. Yet there's a relationship there that wasn't there when the film started, even if it's gone as soon as the ending; like we are Johnny thinking of this trip to London as some fleeting memory from years before. He starts to have sex with a woman at the top of an apartment building before slapping her around and insulting her; yet when Johnny leaves her we can only imagine her life as being what we saw from the window outside: nothing more. Johnny spends some time talking with a night guard, asking him lots of unanswerable questions and eventually ridiculing him about the dead-end nature of his life. The two walk around an office building at night, all the lights on, and if you've ever been to a public office block at night you'll know that feeling of not being with anyone yet somehow not being able to feel alone. The next day when the two meet again in a cafe the man has very little to say to Johnny, other than telling Johnny, simple and straight up "don't waste your life". The first time I watched Naked was a hypnotizing experience, although I didn't enjoy it all that much; Johnny only seemed to ruin lives. He wanted to pull everyone else down to his level, but watching it again I see Johnny isn't trying to ruin any lives because he thinks they've all already been ruined. He does manage to jump start someone's life though, even if we never find out to what extent, which may not be enough to make him a good person but does give him some purpose to go by. He is a Jesus figure in some ways, wanting people to change their lives for the better, only the world he's trying to change no-longer reacts to the promise of a better life or eternal happiness, the only person they do react to is someone who represents themselves at their lowest point.

It's a wordy movie, made up mostly of dialogue from a wide variety of characters who don't stick around long and don't seem to affect much in terms of plot. Yet plot isn't what Naked is about, and neither is it about what makes Johnny tick; as Johnny says at one point "You've had the universe explained to you, and you're bored with it, so now you want cheap thrills and like plenty of them" before walking us through a disposable world where he remains utterly disgusted with everything he see's, and happy to tell everyone about it. It captures a time and place that doesn't seem far away but doesn't exist anymore; that old Britain, not yet commercialized into looking like the rest of the world; it's lots of old fashioned wall papers and yuppy offices. Each person lives in their own little box; the apartment in the film has three people living there but doesn't look lived in at all; it looks temporary, as if all the people living their decided the second they got there that this isn't where they want to stay; Naked is a collection of lives - a lonely night guard, a shy waitress, an easy-going junkie type - that don't feel like they're being lived yet, like they're waiting for a jump start, yet Johnny seems to be the only one who understands that-that jump start isn't coming.

London is painted as an apocalyptic wasteland, each act of unsettling human nature completely ignored by the other happening just a few feet away. All the outdoor scenes look very cold, as if it's the city that's naked; stripped of it's own soul and reduced to accepting the wasteland it's become. Millenium angst looms large, as if the countdown to 1999 has let people live without the same cares as they normally would; this is the setting of The Clash's London Calling, only it's not the government that's pressing down on everyone, the government is invisible here, it's the people themselves; a city eating itself from the inside out. Yet we keep watching Johnny, not because his bleak view lets him see what the people around him don't see, but because even though he's just as lost as everyone around him he seems to care; it would be easy to say he's given up but the torment Johnny looks trapped in stems from a disappointed with the world, and it's only a select few who have the bravery to be disappointed. He has tattered clothes and a messy excess of facial hair and through it all he looks like Jesus, and he wanders around like some sort of messiah; he doesn't give out any answers but looks like he knows them all.

The energy Johnny inspires stems simply from a sense of purpose; he's that magical layabout figure that somehow doesn't seem lost. Johnny's only real possession is his rucksack which as far as we see contains only a small collection of books, Johnny coming across very well read, and sitting there at night watching the movie it made me want to go to the book shelf and start reading right then. Because Johnny's the type of book worm everybody wants to be; not the greying professor but the man who looks like he's been into as many strange worlds as he's read. At one point he finds himself in a woman's house, checking out the book shelf; he tells her about Homer's Odyssey which she owns but hasn't read; it's hard to imagine this man sitting down and reading The Odyssey, instead he comes across as a character who was born already knowing it.

In the best shot of the film Johnny is attacked by a group of youths; they emerge from a dark alley and are masked in silhouette, as if it's the city itself that has swallowed him whole and spat him out a beaten wreck. It's a cruel joke by the filmmakers that we get to know all the characters Johnny meets and annoys, yet it's a nameless group, completely clueless to who Johnny is, that attack him. This sequence always reminds me of a news story from around 10 years ago when Thom Yorke, of Radiohead, was beaten up outside a pub in London. Both men, the real and the fictional, are symbols of angst against the modern world, and these incidents both have these men being beaten up by their own angst; the same world they look down on coming forward and reminding them that they haven't changed it at all and probably never will. That incident can be clearly heard in the sound of Radiohead's album "Hail to the Thief" a peak of paranoia and going off the front cover: capitalist angst. That music would go well with Naked, although even better is the film's melancholic score, which manages to follow Leigh's wonderfully realistic emotional pallet beat-for-beat.

Yet by the end of the film we're at the exact place we started off, more or less, but it feels like we've progressed. Johnny gains nothing from his visit to his ex other than the knowledge of what she's doing now; no relationship after the end credits is pointed to. Yet there's a relationship there that wasn't there when the film started, even if it's gone as soon as the ending; like we are Johnny thinking of this trip to London as some fleeting memory from years before. He starts to have sex with a woman at the top of an apartment building before slapping her around and insulting her; yet when Johnny leaves her we can only imagine her life as being what we saw from the window outside: nothing more. Johnny spends some time talking with a night guard, asking him lots of unanswerable questions and eventually ridiculing him about the dead-end nature of his life. The two walk around an office building at night, all the lights on, and if you've ever been to a public office block at night you'll know that feeling of not being with anyone yet somehow not being able to feel alone. The next day when the two meet again in a cafe the man has very little to say to Johnny, other than telling Johnny, simple and straight up "don't waste your life". The first time I watched Naked was a hypnotizing experience, although I didn't enjoy it all that much; Johnny only seemed to ruin lives. He wanted to pull everyone else down to his level, but watching it again I see Johnny isn't trying to ruin any lives because he thinks they've all already been ruined. He does manage to jump start someone's life though, even if we never find out to what extent, which may not be enough to make him a good person but does give him some purpose to go by. He is a Jesus figure in some ways, wanting people to change their lives for the better, only the world he's trying to change no-longer reacts to the promise of a better life or eternal happiness, the only person they do react to is someone who represents themselves at their lowest point.

Thursday, 14 November 2013

Depressing Music

Around two weeks ago I came in from my first driving lesson, it having taken much less than the duration of one lesson to figure out driving doesn't come naturally to me. Or more precisely: I'm shit at driving, which put me in a mood for the rest of the day. I mostly just moped for the night; glued to a computer screen accomplishing very little, and listening to my new musical obsession, which I had discovered only that day, The Smiths.

My mother had recommend me The Smiths, which seemed good going off the strength of Elvis Costello, her previous musical recommendation. She advertised them to me telling me they had really depressing lyrics, which she found funny, which to be perfectly honest left me indifferent. Since then I've been making my way through their albums chronologically, so far listening to The Smiths and Meat is Murder, two very good albums.

My favorite song of theirs so far is "You've Got Everything Now" which has Morrisey throwing out such gleeful phrasings as "Oh what a terrible mess I've made of my life" and "I've never had a job because I'm too shy". Hell, even the romantic lines are bleak: "I've seen you smile, but I've never heard you laugh". They freaked me out a little on the first listen due to the bluntness; it was actually Johnny Marr's guitar work that had me listening on repeat. The hook is addictive and as the riff picks up towards the end the whole thing starts to feel uplifting. Not happy uplifting, but certainly a bright light at the end of the tunnel each Smiths song creates. It's an obviously weird combination; the music is very R.E.M while the singing and lyrics feel very Ian Curtis, yet it's that combination that has made me make Smiths listening a daily thing.

But it was impossible for me to listen to The Smiths and not start wondering about depressing music. Of which is there is so much. I don't believe depressing music is just for depressed people, mainly because that's not all there is to it; certainly people like to just rock out or admire, but so many people claim they listen to Joy Division or Nirvana or Alice In Chains because they relate, that they find solace in knowing people feel like they do. Only I don't believe this; people do feel better in the knowledge someone was sad just like them, and they probably release something hearing Johnny Rotten being just as fed up as them, but I don't believe that's it, I don't believe it's all about the people; I really do believe "depressing music", even it's very sound, does help people in some way.

Going back to that shitty day coming back from driving I could have very easily put on Katy Perry or Taylor Swift, or even The Rolling Stones or Outkast; serious artists but in no way depressing, but I didn't. I would have been listening to "22" or "Roar" and I would feel excluded from it all, not because the sound is vibrant and happy, but because that music tells you so simply what it is. There's no mistaking it for anything but cheesy, throwaway, very optimistic, party pop. The Smiths don't sound like this at all, they sound uplifting and suicidal all at the same time. I would listen to "You've Got Everything Now" just hoping to reach that high off of the guitar riff. Eventually I became numb to the other lyrics, and the depressing vibe of the verses. It felt like I had conquered the song, that I had made it uplifting despite what it very clearly was.

People say people suffering depression see things more realistically; that they skip past the usual bullshit and don't bother with the surface happiness because it's usually fake and manufactured. That's why the Smiths, and all depressing music, is great: because it doesn't offer happiness but it has the potential for. Most "happy" songs work by themselves but depressing music doesn't, it needs part of the person listening to work. That's why listening to this sort of music in a group doesn't really work; because it's hard to give away part of yourself while there's other people there. I'm not sure if "You've Got Everything Now" really picked me up that day, but it let me in, and let me be depressed with no questions asked.

My mother had recommend me The Smiths, which seemed good going off the strength of Elvis Costello, her previous musical recommendation. She advertised them to me telling me they had really depressing lyrics, which she found funny, which to be perfectly honest left me indifferent. Since then I've been making my way through their albums chronologically, so far listening to The Smiths and Meat is Murder, two very good albums.

My favorite song of theirs so far is "You've Got Everything Now" which has Morrisey throwing out such gleeful phrasings as "Oh what a terrible mess I've made of my life" and "I've never had a job because I'm too shy". Hell, even the romantic lines are bleak: "I've seen you smile, but I've never heard you laugh". They freaked me out a little on the first listen due to the bluntness; it was actually Johnny Marr's guitar work that had me listening on repeat. The hook is addictive and as the riff picks up towards the end the whole thing starts to feel uplifting. Not happy uplifting, but certainly a bright light at the end of the tunnel each Smiths song creates. It's an obviously weird combination; the music is very R.E.M while the singing and lyrics feel very Ian Curtis, yet it's that combination that has made me make Smiths listening a daily thing.

But it was impossible for me to listen to The Smiths and not start wondering about depressing music. Of which is there is so much. I don't believe depressing music is just for depressed people, mainly because that's not all there is to it; certainly people like to just rock out or admire, but so many people claim they listen to Joy Division or Nirvana or Alice In Chains because they relate, that they find solace in knowing people feel like they do. Only I don't believe this; people do feel better in the knowledge someone was sad just like them, and they probably release something hearing Johnny Rotten being just as fed up as them, but I don't believe that's it, I don't believe it's all about the people; I really do believe "depressing music", even it's very sound, does help people in some way.

Going back to that shitty day coming back from driving I could have very easily put on Katy Perry or Taylor Swift, or even The Rolling Stones or Outkast; serious artists but in no way depressing, but I didn't. I would have been listening to "22" or "Roar" and I would feel excluded from it all, not because the sound is vibrant and happy, but because that music tells you so simply what it is. There's no mistaking it for anything but cheesy, throwaway, very optimistic, party pop. The Smiths don't sound like this at all, they sound uplifting and suicidal all at the same time. I would listen to "You've Got Everything Now" just hoping to reach that high off of the guitar riff. Eventually I became numb to the other lyrics, and the depressing vibe of the verses. It felt like I had conquered the song, that I had made it uplifting despite what it very clearly was.

People say people suffering depression see things more realistically; that they skip past the usual bullshit and don't bother with the surface happiness because it's usually fake and manufactured. That's why the Smiths, and all depressing music, is great: because it doesn't offer happiness but it has the potential for. Most "happy" songs work by themselves but depressing music doesn't, it needs part of the person listening to work. That's why listening to this sort of music in a group doesn't really work; because it's hard to give away part of yourself while there's other people there. I'm not sure if "You've Got Everything Now" really picked me up that day, but it let me in, and let me be depressed with no questions asked.

Sunday, 10 November 2013

Loosing Your (Singing) Voice

I sang as a child, maybe not a lot or not a lot for what the average child sings, but I did sing. I don't sing anymore because that scares me, to sing in public would only be forgotten by everyone there in a matter of minutes but the embarrassment would stick in my head for a long time, years maybe, or at probable worst all my life. But as a kid you don't give a fuck, not because your confident, which you appear, or because you think your good, which if you do or don't slips my mind, but because you have no way of knowing the social consequences. For the best people those don't exist anyway, but for the rest of us we don't sing in public. I can't handle any audience, not even myself. I tried to sing alone not too long ago, nothing operatic, some Nirvana, after all most people can't even tell what the lyrics of Teen Spirit are. But I sucked, I hated it and it made me swear to myself, without anything internal or external actually being said, to never sing again.

I only remember singing once as a child, in first school, two years before year one or "first grade" in what my school tagged "nursery". I sang ABBA (What else?) and don't remember the reaction whatsoever. I was instructed specifically at the start to not sing ABBA but I didn't know anything else. The song? Dancing Queen. Or Super Trooper. Maybe Mamma Mia. Lets hope to fuck it wasn't Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) but I wouldn't guess against it. The singing voice, which was summoned without thinking and with no ambition for professionalism must have been somewhat horrible, but I bet you your fucking house my enthusiasm came through. The sort only a real fan could summon. I couldn't do that with any band today, not Nirvana or Eminem or Outkast but I did it then for ABBA who had been programmed into my brain like an electronic chip.

And I bet you I didn't go up and down with the music, not in the same tones that the real singers did. I would have known the way they sang each syllable off by heart, at least if a four year old's brain can pick that stuff up, but I would have just tried to get the words out. All in my accent in my un self-aware four year old's voice. And it's easier to relate to singing that is someone singing what comes from them, singing it the way it comes out, than singing it the way they think it should be sang. In "Lucille" by Little Richard the man sings the line "I'll be good to you baby, please don't leave me alone" three times. On the first and third he says it too fast, it sounds like a mistake. You can tell what he's saying but it sounds like it's come out wrong while he tries to remember the words. But the second time it comes out perfectly; all the words are separate entities. The difference is noticeable, and it makes you hear him put emphasis on some words, it puts your attention on how he says things, not what he's saying. And Little Richard always got this, you can hear him trying to do this and that, like a craftsman fiddling away at work before your eyes and not like a piece of pre-created product that's already been worked out.

The Elvis version of Tutti Fruitti" doesn't work because he sings it too fast. In "Hound Dog" he adds a crackle to the singing but in Fruitti he's just imitating the black music that inspired him. The Little Richard (y'know, cos he rocks) version stretches it out just this bit longer. You can imagine little richie's body shaking along, but Elvis would have to go into spasm just to keep up with his version.

Singing comes straight from our bodies, unlike a guitar or keyboard which needs an instrument and an exclusive school of talent and training, but we can all sing, and we can all sing masterful lyrics, but none of us who aren't pros can whip out a guitar and fire out a ballad, not even a simple one. Singing is the most human part of music, the one we all feel like we can do ourself. In the movies the tragic hero who dreams of being in a rock band but can't cut it sits and uses a hair brush in place of a microphone and pretends to sing while David Bowie comes through the speakers. The nerdy kid in the teen comedy evokes the laughs because he's air guitaring. You can't hear personality, who a person really is beyond their immediate talent, from a miracle of a high note, but you can hear Little Richard, who he really is even if we never meet him and know him as a person, in those three verses.

When Mick Jagger first appeared in the early 60s it was like a floodgate opening, moving as far away as we could from opera singers and the low-baritone vocals of 50s rock'n'roll. Jagger's voice started out like an imitation of these singers - just listen to their first single "Come On" - but soon his accent really came through. It lurched left and right, more than older singers would have ever allowed, or would have been allowed to, but Jagger put a personality into the singing, which made sense when he and Keith Richard started writing songs; the lines were much longer yet the singing slower. Lou Reed, who inspired this post, perfected conversational singing. In "Sweet Jane" the lines don't even rhyme but they go with the music. By then it was hardly even singing, the lyrics simply fit the bill in the form they came out.

But Reed didn't sing all the Velvet Underground songs, and any band would be lucky to have a voice as unique as Mo Tucker's sitting at the back. "After Hours" and "I'm Sticking with You" are more for Tucker's voice than anything else. It's a gimmick for sure, but people do gimmicky shit with instruments and recording equipment all the time, the voice is no different. Surely The Kingsmen's "Louie Louie" could be called genius, sang in complete garble, almost drunk sounding. It's the full acceptance of the voice as another tool. When "Smells Like Teen Spirit" released a few decades later the comparison was easy, but my favorite thing about most Nirvana songs is trying to work out the lyrics. For years I thought the line "And I swear I don't have a gun" was "I swear I don't have a god" to me it wasn't depressingly ironic, just punk rebellious. When Kurt Cobain sang a line it didn't rhyme because the words ended the same but because the general sound coming out of his mouth was pretty similar to the last. The lyrics themselves didn't matter in the moment; you got the emotion from his voice.

Yet now so few singers see voice as the same musical opportunity that Little Richard did, or the same wavering conversational piece that Lou Reed did; they don't use it as flexibly as Freddie Mercury did or use it with such power, personal power, as Michael Jackson did (or at least 80s Jacko did). Actually when was the last time you heard a rock musician really use their voice, and put it in the center alongside the guitars or drums or piano or whatever. Chris Martin stays in one tone, Arcade Fire all blurs together, and I don't even know if Alex Turner can get angry. Most other genres don't make much difference; rap and hip-hop has started sounding samey and is there any point bringing up mainstream pop?

Which isn't to say these guys are bad; Alex Turner has went from a typical Liverpool accent (used to create a conversational style on their debut album) to a smoother, more romanticized voice. Most of these singers seem more than serviceable, to the point they project across a stadium perfectly, something that Jagger always struggled to do. And there's some that seem to actually alter their singing voices: Kanye West is the best example. Which should be expected from such a studio-focused artist. He used auto-tune to purposefully emotionless effect on 808s and Heartbreak and in this years "Blood On The Leaves" he let the grand emotion in his voice entangle with the technology. Eminem doing his sarcastic singing, doing the full white trash, at the beginning of "So Far" is a good example of someone using their voice, someone who said himself he couldn't sing no less.

This wasn't about auto-tune. Mainly because this wasn't about note-perfect singing. Singing usually isn't the thing that draws people into music, it's not what makes people want to be rockstars. That's the guitar sounds and the lyrics you go over and over in your head. Mick Jagger's stage persona becomes an attachment of the singing, and that sure looks cool doesn't it? No, singing, the kind which was the mainstream only a few decades ago, wasn't about beautiful sound, it was about people who hadn't aimed to be singers being singers and bringing themselves into it. The singing would tell you more about the artist than the words did.

I only remember singing once as a child, in first school, two years before year one or "first grade" in what my school tagged "nursery". I sang ABBA (What else?) and don't remember the reaction whatsoever. I was instructed specifically at the start to not sing ABBA but I didn't know anything else. The song? Dancing Queen. Or Super Trooper. Maybe Mamma Mia. Lets hope to fuck it wasn't Gimme Gimme Gimme (A Man After Midnight) but I wouldn't guess against it. The singing voice, which was summoned without thinking and with no ambition for professionalism must have been somewhat horrible, but I bet you your fucking house my enthusiasm came through. The sort only a real fan could summon. I couldn't do that with any band today, not Nirvana or Eminem or Outkast but I did it then for ABBA who had been programmed into my brain like an electronic chip.

And I bet you I didn't go up and down with the music, not in the same tones that the real singers did. I would have known the way they sang each syllable off by heart, at least if a four year old's brain can pick that stuff up, but I would have just tried to get the words out. All in my accent in my un self-aware four year old's voice. And it's easier to relate to singing that is someone singing what comes from them, singing it the way it comes out, than singing it the way they think it should be sang. In "Lucille" by Little Richard the man sings the line "I'll be good to you baby, please don't leave me alone" three times. On the first and third he says it too fast, it sounds like a mistake. You can tell what he's saying but it sounds like it's come out wrong while he tries to remember the words. But the second time it comes out perfectly; all the words are separate entities. The difference is noticeable, and it makes you hear him put emphasis on some words, it puts your attention on how he says things, not what he's saying. And Little Richard always got this, you can hear him trying to do this and that, like a craftsman fiddling away at work before your eyes and not like a piece of pre-created product that's already been worked out.

The Elvis version of Tutti Fruitti" doesn't work because he sings it too fast. In "Hound Dog" he adds a crackle to the singing but in Fruitti he's just imitating the black music that inspired him. The Little Richard (y'know, cos he rocks) version stretches it out just this bit longer. You can imagine little richie's body shaking along, but Elvis would have to go into spasm just to keep up with his version.

Singing comes straight from our bodies, unlike a guitar or keyboard which needs an instrument and an exclusive school of talent and training, but we can all sing, and we can all sing masterful lyrics, but none of us who aren't pros can whip out a guitar and fire out a ballad, not even a simple one. Singing is the most human part of music, the one we all feel like we can do ourself. In the movies the tragic hero who dreams of being in a rock band but can't cut it sits and uses a hair brush in place of a microphone and pretends to sing while David Bowie comes through the speakers. The nerdy kid in the teen comedy evokes the laughs because he's air guitaring. You can't hear personality, who a person really is beyond their immediate talent, from a miracle of a high note, but you can hear Little Richard, who he really is even if we never meet him and know him as a person, in those three verses.

When Mick Jagger first appeared in the early 60s it was like a floodgate opening, moving as far away as we could from opera singers and the low-baritone vocals of 50s rock'n'roll. Jagger's voice started out like an imitation of these singers - just listen to their first single "Come On" - but soon his accent really came through. It lurched left and right, more than older singers would have ever allowed, or would have been allowed to, but Jagger put a personality into the singing, which made sense when he and Keith Richard started writing songs; the lines were much longer yet the singing slower. Lou Reed, who inspired this post, perfected conversational singing. In "Sweet Jane" the lines don't even rhyme but they go with the music. By then it was hardly even singing, the lyrics simply fit the bill in the form they came out.

But Reed didn't sing all the Velvet Underground songs, and any band would be lucky to have a voice as unique as Mo Tucker's sitting at the back. "After Hours" and "I'm Sticking with You" are more for Tucker's voice than anything else. It's a gimmick for sure, but people do gimmicky shit with instruments and recording equipment all the time, the voice is no different. Surely The Kingsmen's "Louie Louie" could be called genius, sang in complete garble, almost drunk sounding. It's the full acceptance of the voice as another tool. When "Smells Like Teen Spirit" released a few decades later the comparison was easy, but my favorite thing about most Nirvana songs is trying to work out the lyrics. For years I thought the line "And I swear I don't have a gun" was "I swear I don't have a god" to me it wasn't depressingly ironic, just punk rebellious. When Kurt Cobain sang a line it didn't rhyme because the words ended the same but because the general sound coming out of his mouth was pretty similar to the last. The lyrics themselves didn't matter in the moment; you got the emotion from his voice.

Yet now so few singers see voice as the same musical opportunity that Little Richard did, or the same wavering conversational piece that Lou Reed did; they don't use it as flexibly as Freddie Mercury did or use it with such power, personal power, as Michael Jackson did (or at least 80s Jacko did). Actually when was the last time you heard a rock musician really use their voice, and put it in the center alongside the guitars or drums or piano or whatever. Chris Martin stays in one tone, Arcade Fire all blurs together, and I don't even know if Alex Turner can get angry. Most other genres don't make much difference; rap and hip-hop has started sounding samey and is there any point bringing up mainstream pop?

Which isn't to say these guys are bad; Alex Turner has went from a typical Liverpool accent (used to create a conversational style on their debut album) to a smoother, more romanticized voice. Most of these singers seem more than serviceable, to the point they project across a stadium perfectly, something that Jagger always struggled to do. And there's some that seem to actually alter their singing voices: Kanye West is the best example. Which should be expected from such a studio-focused artist. He used auto-tune to purposefully emotionless effect on 808s and Heartbreak and in this years "Blood On The Leaves" he let the grand emotion in his voice entangle with the technology. Eminem doing his sarcastic singing, doing the full white trash, at the beginning of "So Far" is a good example of someone using their voice, someone who said himself he couldn't sing no less.

This wasn't about auto-tune. Mainly because this wasn't about note-perfect singing. Singing usually isn't the thing that draws people into music, it's not what makes people want to be rockstars. That's the guitar sounds and the lyrics you go over and over in your head. Mick Jagger's stage persona becomes an attachment of the singing, and that sure looks cool doesn't it? No, singing, the kind which was the mainstream only a few decades ago, wasn't about beautiful sound, it was about people who hadn't aimed to be singers being singers and bringing themselves into it. The singing would tell you more about the artist than the words did.

Tuesday, 5 November 2013

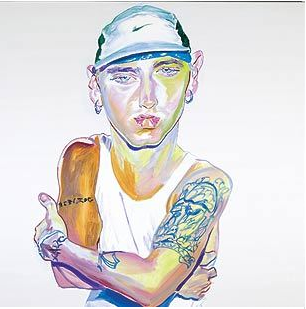

Eminem: The Marshall Mathers LP2 Review

Out of all of the things my mind drifts to when left alone, what major force will rule art after post-modernism seems to be coming up a lot lately, and such a change must be due soon, right? The official term is apparently quasi-modernism, a response to the self-questioning nature of the current world in which art will move away from irony and individuality and go back to a more sure state. Eminem, who's success was born during the millenium angst era (blatant post-modernism's creative and commercial peak) used his stance as the biggest rapper (the most self-referential of all genres) of the time, or maybe even biggest artist of the time, to mock his own fame (and the famous around him) and confuse his image with the contradictions of Marshall Mathers, Slim Shady and Eminem. Yet Marshall Mathers LP2 is more like post-post-modernism; even it's name a spiral into the many nostalgic references that appear on the album.

Post-modernism came to major prominence, at least in the arts, during the 60s. The films of the french new-wave aimed to show the banal constructions of the movies Hollywood was churning out, and the James Bond franchise accepted the lunacy of the movies and just ran with it. Modernist films didn't work anymore; they didn't wink at their own absurdity - or bypass it completely - like these new movies did. It's harder to pinpoint music's evolution into a post-modern state; although the 60s too moved people away completely from the craftsmanship of classical compositions and let them see the real people striving to create their own personal masterpieces. This culture has of course exploded since then; the bubble burst in 2000 and since then no-one can even be influenced because everyone's influenced by everyone, and opinion's don't matter because everyone opinion imaginable has been posted online. Eminem, in response to his post-modern born success has spent the last few years almost regressing away from it, accepting his own position as king in the land of music, and making albums that look inside and aim for a more commercial, technically impressive sound. Yet his last two albums came off boring, a once hilariously punk artist "maturing" in all the wrong ways; yet looking back they don't seem stagnant from Eminem's lack of creativity but because he had too much: too many options, too many things that could be said, and too many ways people could react.

LP2 shoots off in so many directions that it has no image, although that doesn't mean it's directionless; it almost goes so far as to make fun of any art that has an image, of any art that doesn't self-comment on it's own self-commenting nature. LP2 has all sides of Eminem: the scary murderous Eminem last seen on the first LP ("My life will be so much better if you just dropped dead") self-hating Eminem ("Came to the world at a time when it was in need of a villain/An asshole, that role I think I succeed in fulfilling") pop Eminem (solidified by "Survival" created for the new Call of Duty, which works better without the 3 minute product placement of a video) and even the more ambitious, technical Eminem of recent times (the hyper-speed rapping of "Rap God" will be admirable to people not even well-versed in the genre). Eminem mixes in everything he can from his 10+ year reign, right from his references to Bill Clinton to his throwbacks to ex-wife Kim right to his claims that this is album is "the end of a saga" as if by putting all those thoughts in his head, those endless thoughts everyone one of the internet age and the gossip culture is forever flooded by, into one album, that maybe he can move past it and grow up. It creates an urgency to this album, more so than any other Eminem album, as if it's very creation is important to it's creator.

"Goofy" Eminem also shows up; if the other tracks all position Eminem as the center of the universe then these tracks take him back to a white trash american hip-hop kid on the streets, only a little faster paced and more confident. The best track to come of this is "So Far", also the best track on the album, where Eminem describes, among many other things, not being able to go into a restroom in McDonald's without being bothered because of his celebrity. Em switches from playing stupid with a groovy backing track (proving Eminem can write a hilarious track without the need for shock value) to vintage celebrity-hating anger with a guitar backing track.

Yet this offshoot of different styles would simply come off schizophrenic if the production didn't back it up. The disc is produced by Dr. Dre and Rick Rubin and the production creates a claustrophobic feeling, giving little space from song to song; no chance to breath or question where the album is going. The backing tracks don't stray too far from what was found on Em's tracks 10 years ago, although the sampling used is a mixed bag; "Berzerk" uses samples from Billy Squier's "The Stroke" and two from the Beastie Boys' first album. These work in the sense they add to the rap; the song was clearly written around them and would feel incomplete without them, yet in "Rhyme Or Reason" when the song is scored to The Zombies' "Time of the Season" it feels forced and Eminem almost manages to get lost in the mix at times. Although that shouldn't take away from what is for the most part a fantastic production; lots of great tricks but few of them ever intruding on the track. The indulgences: a fake news report that opens "Brainless", a sampling of "The Real Slim Shady" in "So Far" etc feel organic to Em's own mission to create his own murderous image; the opposite of the weird production effects of Kanye West's Yeezus, which's production seemed to dictate as much of the album as the music did (and to great results, I should mention).

The guest list doesn't appear as eccentric as you might expect. Kendrick Lamar, appearing on "Love Game" another highlight, is the best of the bunch, working against his normal pop attitude. Yet there is something noticeable about the way Eminem uses, and has always used, his female guests. Unlike the male guests, like Lamar, who organically come in and out of the track alongside Em as if it is as much their track as his, the female guests are sectioned off from Em's rap, as if as much a usable tool for the benefit of the track as much as the samples of songs over 20 years old. Skylar Grey appears on "Asshole" but is wooden, and a feels purposefully wooden; she adds to the track but has little place of her own in it. Em's best female duet was with Rihanna in "Love the Way You Lie" where both brought their different styles into the track. He re-teams with Rihanna here on "The Monster", a simple, catchy pop tune, aided by Rihanna who does little but play her part as instructed: repeating the chorus as required. Em still hasn't figured out, or maybe just plucked up the courage, to share control of a track with a woman. Yet it's Eminem himself who puts in the best performance here; his best in years. In the past few years I've likened him to Tiger Woods in which the golf champ played himself into boredom; no longer even registering as an interesting player. Since his comeback Eminem has seemed like that too; although there's a sense of fun to the raps here; as if there's something to prove again. There's a show-off style to the rapping, as if it's finally acceptable to be openly good at things again. The sarcastic digs and smart quips throughout the album should go up there with the man's best.

In the end it's impossible to get to the end of LP2 without questioning what you've learnt about Eminem on the way; and I don't mean the alter-ego's he conjures up: I mean the real Eminem. The closest comparison to Eminem's stories in which he wants us to see him as a fame-hating murderer is the life-as-performance-art of Kanye West. Yet West has kept it all up; I don't know if West is really an asshole but he's given me no other alternative but to believe it. Yet we've all seen the good in Eminem; ambitious but not quite arrogant, and very probably fame-hating but in a funny way and not as spiteful as in the songs. We know about Eminem's family and his retirement from music, and through all of the years the story Em told in "Kim" his most disturbing story, became only fantasy, yet it was made as fact. LP2 is the first time Eminem has accepted it all as fantasy, and what we get is someone playing with their own image and having a lot of fun with it. If you do need to single this disc down to one single Eminem it's "messy" Eminem, who here has made what is undoubtedly Em's most like-able disc yet.

Post-modernism came to major prominence, at least in the arts, during the 60s. The films of the french new-wave aimed to show the banal constructions of the movies Hollywood was churning out, and the James Bond franchise accepted the lunacy of the movies and just ran with it. Modernist films didn't work anymore; they didn't wink at their own absurdity - or bypass it completely - like these new movies did. It's harder to pinpoint music's evolution into a post-modern state; although the 60s too moved people away completely from the craftsmanship of classical compositions and let them see the real people striving to create their own personal masterpieces. This culture has of course exploded since then; the bubble burst in 2000 and since then no-one can even be influenced because everyone's influenced by everyone, and opinion's don't matter because everyone opinion imaginable has been posted online. Eminem, in response to his post-modern born success has spent the last few years almost regressing away from it, accepting his own position as king in the land of music, and making albums that look inside and aim for a more commercial, technically impressive sound. Yet his last two albums came off boring, a once hilariously punk artist "maturing" in all the wrong ways; yet looking back they don't seem stagnant from Eminem's lack of creativity but because he had too much: too many options, too many things that could be said, and too many ways people could react.

LP2 shoots off in so many directions that it has no image, although that doesn't mean it's directionless; it almost goes so far as to make fun of any art that has an image, of any art that doesn't self-comment on it's own self-commenting nature. LP2 has all sides of Eminem: the scary murderous Eminem last seen on the first LP ("My life will be so much better if you just dropped dead") self-hating Eminem ("Came to the world at a time when it was in need of a villain/An asshole, that role I think I succeed in fulfilling") pop Eminem (solidified by "Survival" created for the new Call of Duty, which works better without the 3 minute product placement of a video) and even the more ambitious, technical Eminem of recent times (the hyper-speed rapping of "Rap God" will be admirable to people not even well-versed in the genre). Eminem mixes in everything he can from his 10+ year reign, right from his references to Bill Clinton to his throwbacks to ex-wife Kim right to his claims that this is album is "the end of a saga" as if by putting all those thoughts in his head, those endless thoughts everyone one of the internet age and the gossip culture is forever flooded by, into one album, that maybe he can move past it and grow up. It creates an urgency to this album, more so than any other Eminem album, as if it's very creation is important to it's creator.

"Goofy" Eminem also shows up; if the other tracks all position Eminem as the center of the universe then these tracks take him back to a white trash american hip-hop kid on the streets, only a little faster paced and more confident. The best track to come of this is "So Far", also the best track on the album, where Eminem describes, among many other things, not being able to go into a restroom in McDonald's without being bothered because of his celebrity. Em switches from playing stupid with a groovy backing track (proving Eminem can write a hilarious track without the need for shock value) to vintage celebrity-hating anger with a guitar backing track.

Yet this offshoot of different styles would simply come off schizophrenic if the production didn't back it up. The disc is produced by Dr. Dre and Rick Rubin and the production creates a claustrophobic feeling, giving little space from song to song; no chance to breath or question where the album is going. The backing tracks don't stray too far from what was found on Em's tracks 10 years ago, although the sampling used is a mixed bag; "Berzerk" uses samples from Billy Squier's "The Stroke" and two from the Beastie Boys' first album. These work in the sense they add to the rap; the song was clearly written around them and would feel incomplete without them, yet in "Rhyme Or Reason" when the song is scored to The Zombies' "Time of the Season" it feels forced and Eminem almost manages to get lost in the mix at times. Although that shouldn't take away from what is for the most part a fantastic production; lots of great tricks but few of them ever intruding on the track. The indulgences: a fake news report that opens "Brainless", a sampling of "The Real Slim Shady" in "So Far" etc feel organic to Em's own mission to create his own murderous image; the opposite of the weird production effects of Kanye West's Yeezus, which's production seemed to dictate as much of the album as the music did (and to great results, I should mention).

The guest list doesn't appear as eccentric as you might expect. Kendrick Lamar, appearing on "Love Game" another highlight, is the best of the bunch, working against his normal pop attitude. Yet there is something noticeable about the way Eminem uses, and has always used, his female guests. Unlike the male guests, like Lamar, who organically come in and out of the track alongside Em as if it is as much their track as his, the female guests are sectioned off from Em's rap, as if as much a usable tool for the benefit of the track as much as the samples of songs over 20 years old. Skylar Grey appears on "Asshole" but is wooden, and a feels purposefully wooden; she adds to the track but has little place of her own in it. Em's best female duet was with Rihanna in "Love the Way You Lie" where both brought their different styles into the track. He re-teams with Rihanna here on "The Monster", a simple, catchy pop tune, aided by Rihanna who does little but play her part as instructed: repeating the chorus as required. Em still hasn't figured out, or maybe just plucked up the courage, to share control of a track with a woman. Yet it's Eminem himself who puts in the best performance here; his best in years. In the past few years I've likened him to Tiger Woods in which the golf champ played himself into boredom; no longer even registering as an interesting player. Since his comeback Eminem has seemed like that too; although there's a sense of fun to the raps here; as if there's something to prove again. There's a show-off style to the rapping, as if it's finally acceptable to be openly good at things again. The sarcastic digs and smart quips throughout the album should go up there with the man's best.

In the end it's impossible to get to the end of LP2 without questioning what you've learnt about Eminem on the way; and I don't mean the alter-ego's he conjures up: I mean the real Eminem. The closest comparison to Eminem's stories in which he wants us to see him as a fame-hating murderer is the life-as-performance-art of Kanye West. Yet West has kept it all up; I don't know if West is really an asshole but he's given me no other alternative but to believe it. Yet we've all seen the good in Eminem; ambitious but not quite arrogant, and very probably fame-hating but in a funny way and not as spiteful as in the songs. We know about Eminem's family and his retirement from music, and through all of the years the story Em told in "Kim" his most disturbing story, became only fantasy, yet it was made as fact. LP2 is the first time Eminem has accepted it all as fantasy, and what we get is someone playing with their own image and having a lot of fun with it. If you do need to single this disc down to one single Eminem it's "messy" Eminem, who here has made what is undoubtedly Em's most like-able disc yet.

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)